1.2 — Scarcity, Choice, and Cost

ECON 306 • Microeconomic Analysis • Fall 2020

Ryan Safner

Assistant Professor of Economics

safner@hood.edu

ryansafner/microF20

microF20.classes.ryansafner.com

The Logic of Choice

The Logic of Choice: Ends and Means

Each of us acts purposefully

We have ends, goals, desires, objectives, etc

We use means in the world that we believe will achieve our ends

The Logic of Choice: Purpose

Acting with purpose distinguishes humans from everything else in the universe

Artificial intelligence researchers face "the frame problem"

- We thought: computation is hard, perception is easy

- We've found: computation is easy, perception is hard!

Causal Inference I

- Machine learning and artificial intelligence are "dumb"1

- With the right models and research designs, we can say "X causes Y" and quantify it!

- Economists are in a unique position to make causal claims that mere statistics cannot

1 For more, see my blog post, and Pearl & MacKenzie (2018), The Book of Why

Causal Inference II

"First, the field of economics has spent decades developing a toolkit aimed at investigating empirical relationships, focusing on techniques to help understand which correlations speak to a causal relationship and which do not. This comes up all the time — does Uber Express Pool grow the full Uber user base, or simply draw in users from other Uber products? Should eBay advertise on Google, or does this simply syphon off people who would have come through organic search anyway? Are African-American Airbnb users rejected on the basis of their race? These are just a few of the countless questions that tech companies are grappling with, investing heavily in understanding the extent of a causal relationship."

Methodological Individualism

Only individual people act

The individual is the base unit of all economic analysis

"How will action/choice/policy/institution [X] affect each individual's well-being?"

Goods and Services

Actions that satisfy human desires provide a service

An object that can provide services is called an economic good or a resource

Consumption

- Goods and services provide "utility" (satisfaction of a desire) when we consume them

Bads

- An economic bad is something that hinders our ability to satisfy our desires

Scarcity and Its Economic Implications

Scarcity

Scarcity: human desires are practically unlimited, but our ability to satisfy them (with goods and services) is limited

How do we best economize limited resources to satisfy our unlimited desires "efficiently?"

Choice

We can only pursue one goal at a time

This implies that we must choose to forgo all other alternatives when we pursue each goal

Choice → Opportunity Cost

We can only pursue one goal at a time

This implies that we must choose to forgo all other alternatives when we pursue each goal

The (opportunity) cost of every choice is the next best alternative given up

- "You can't have your cake and eat it too"

The Parable of the Broken Window

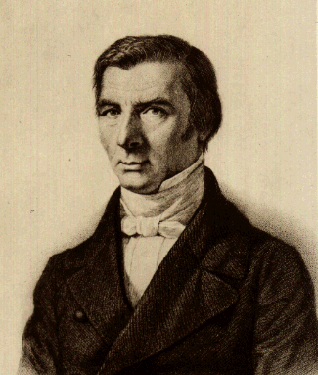

Frederic Bastiat

1801-1850

- That Which is Seen and That Which is Not Seen

The Parable of the Broken Window

Frederic Bastiat

1801-1850

That Which is Seen and That Which is Not Seen

"That which is seen"

- The broken window

- Resources diverted into glassmaking

The Parable of the Broken Window

Frederic Bastiat

1801-1850

That Which is Seen and That Which is Not Seen

"That which is seen"

- The broken window

- Resources diverted into glassmaking

"That which is not seen"

- Opportunity cost of fixing the window

- Resources diverted away from other opportunities

Applying the Parable of the Broken Window

- What does it mean to say that "spending money 'stimulates' the economy"?

Applying the Parable of the Broken Window

What does it mean to say that "spending money 'stimulates' the economy"?

Scarce resources used in one industry can not be used in other industries

Every (visible) decision to spend on X yields more X, and destroys an (invisible) opportunity to spend on Y

Where Do Goods Get Their Value?

A Theory of Value

"Classical Economists" (c. 1776-1870)

Goods have "natural" prices, determined objectively by cost of production (wages+rents+profits)

- Labor theory of value: prices of goods determined by amount of "labor hours" to make

A Paradox!

The Solution (1870s)

The Marginalist Revolution

All human choices are made "on the margin, considering a small change from your current situation

Buying, selling, consuming, or producing a discrete unit of a particular good at a time

Each unit of a good consumed provides marginal utility

Marginalism

Carl Menger

1840-1921

Value is thus nothing inherent in goods, no property of them, nor an independent thing existing by itself. It is a judgment economizing men make about the importance of the goods at their disposal for the maintenance of their lives and well-being. Hence, value does not exist outside the consciousness of men (pp. 120-121).

Menger, Carl, 1871, Principles of Economics

Marginal Utility Determines Prices: A Demonstration

Three Insights About Value

Value is subjective

- Each of us has our own preferences that determine our ends or objectives

- Choice is forward looking: a comparison of your expectations about opportunities

Preferences are not comparable across individuals

- Only individuals know what they give up at the moment of choice

Three Insights About Value

- Value is measured as an ordinal concept

- We can rank our objectives relative to each other (but cannot quantify further)

- We pursue highest-valued objectives (highest marginal utility) first

- Pursuing one objective means not pursuing others!

Three Insights About Value

- Value inherently comes from the fact that we must make tradeoffs

- Making one choice means having to give up pursuing others!

- The choice we pursue at the moment must be worth the sacrifice of others! (i.e. highest marginal utility)

Value and the Margin I

The Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility: each marginal unit of a good consumed tends to provide less marginal utility than the previous unit, all else equal

Value and the Margin II

Example: Suppose you have 5 uses for water by their value to you. Assume each use requires exactly 1 gallon of water:

- Drink water

- Take a shower

- Wash car

- Water plants

- Change goldfish's water

Value and the Margin II

Example: Suppose you have 5 uses for water by their value to you. Assume each use requires exactly 1 gallon of water:

- Drink water

- Take a shower

- Wash car

- Water plants

- Change goldfish's water

Suppose you have only 1 gallon of water, what will you do with it?

Value and the Margin II

Example: Suppose you have 5 uses for water by their value to you. Assume each use requires exactly 1 gallon of water:

- Drink water

- Take a shower

- Wash car

- Water plants

- Change goldfish's water

Suppose you have have 2 gallons of water, what will you do with them?

Value and the Margin II

Example: Suppose you have 5 uses for water by their value to you. Assume each use requires exactly 1 gallon of water:

- Drink water

- Take a shower

- Wash car

- Water plants

- Change goldfish's water

Suppose you had 5 gallons of water, but spill one. Which activity will you stop doing?